In my copious spare time, I continue to immerse myself in my favorite field—literature. Most recently: Tolstoy. I am still not man enough to make it through “War and Peace”. I have tried at three separate stages of my life and I have not yet made it past p. 100. Perhaps I will try one more time in the future. But for now, I contented myself with three of his novellas: “The Death of Ivan Ilych”, “The Kreutzer Sonata”, and “Master and Man”.

Take them one at a time: “Ivan Ilych” (1886) relates the terminal illness and eventual death of a powerful legal magistrate, the eponymous Ivan Ilych. He has been an aggressive career seeker but honest, a barrister of integrity. He believes he has lived a good life, so his untimely and agonizing demise is senseless and unjust. His family thinks he is merely sick, and their lack of compassion for his terminal illness frustrates him. The only one who is compassionate to him is his servant, Gerasim. He begins to reflect introspectively on his life and its meaning, or, more accurately, its lack of such. He realizes that living for oneself is empty and that fulfillment comes solely from living for others. Compassion, kindness, and intimacy constitute a meaningful life; no career advance or material gain can compensate for their absence. With this realization, fear of death vanishes—“and in place of death there was light”….”What joy,” he exclaims and dies shortly after.

“The Kreutzer Sonata” (1889), named after a Beethoven composition, is a first person narrative in which the protagonist, Pozdnyshev, tells the story of how and why he murdered his wife. His wife was possibly unfaithful; this is not made clear, but he murders her anyway. The protagonist argues that women will never achieve equal rights as long as men perceive them solely as objects of lustful desire; that, at the same time, their beauty and sex appeal confer on them enormous power over men that most women are loath to relinquish; that carnal desire, even tricked out in Church-sanctioned marriage and the romantic love glorified by poets is “piggish”; and that humans should love God first and humanity second, and reject the selfish hedonism of sexual love. Pozdnyshev was acquitted for the murder of his wife, and seems to regard the “animalistic insanity” of romantic love and attendant jealousy as adequate explanation and perhaps exoneration of his brutal crime.

“Master and Man” (1895) tells the story of an affluent landowner, Brekhunov, and his servant, Nikita. They set out in a blizzard to visit another landowner, so Brekhunov can buy forest land before his competitors do. Though they repeatedly lose the road in the snow and are in danger of freezing, all Brekhunov can think of is the money he will eventually make. Finally, they are lost and must spend the night outdoors. Brekhunov takes the horse and leaves the more lightly garbed Nikita to freeze. But the horse flounders and Brekhunov finds himself back at the sleigh. The master experiences an epiphany: He realizes that the only fulfillment in life consists in living and/or dying for others. Brekhunov lies on top of Nikita and pulls his coat around them, keeping the servant warm. In the morning, the peasants dig out the sleigh and find Brekhunov frozen to death but Nikita alive.

Tolstoy is a writer of great power who abundantly deserves his exalted literary reputation. If we are uncritical regarding his moral themes, it would be easy to dismiss them as crudely self-sacrificial. Except that there is a type of egoism here—for both Ivan Ilych and Brekhunov find a form of blissful fulfillment in serving others (or contemplating it). In truth, there is deep fulfillment in gaining profound intimacy with some of our brothers and sisters. What is profoundly mistaken in Tolstoy’s moral themes is his contention that there is no meaning in “selfish” living—in career success, material wealth well-earned, and romantic love. In fact, there is great joy in a productive career one loves, in honestly earning wealth via that career, and in attaining deep romantic love with a honest man or woman one treasures.

Perhaps the only intimacy that Tolstoy values is that which leads directly to one’s death…rather than to flourishing life. Certainly his bitter harangue against romance in “The Kreutzer Sonata” is vile and drove me immediately back to Rostand’s vivid ode to romantic love, “Cyrano de Bergerac”. As Ayn Rand wrote in “Anthem”: “…to hold the body of women in our arms is neither ugly nor shameful, but the one ecstasy granted to the race of men.”

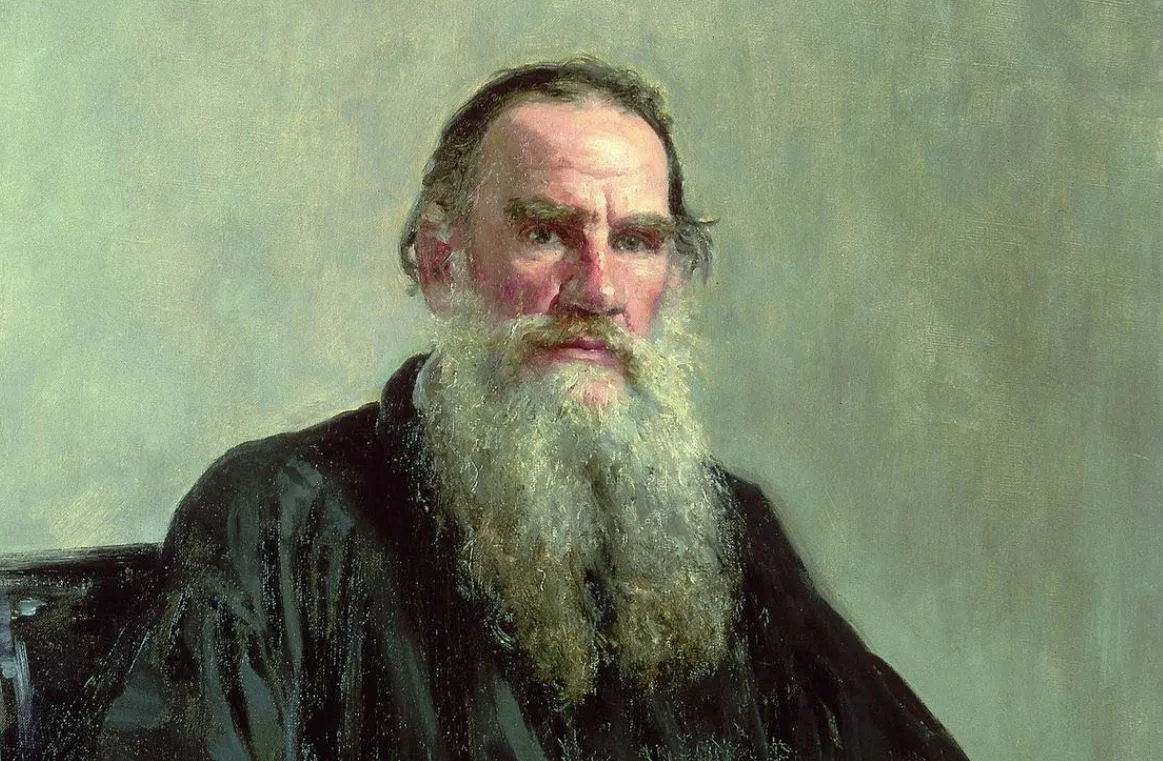

Final assessment: Tolstoy is philosophically mistaken, morally complex but generally despicable, psychologically masterful, and literarily brilliant. Tolstoy dramatizes his themes, he does not merely talk about them. One need not agree with a great writer’s theme(s) to appreciate the exalted quality of his artistry. No one exemplifies this truth more fulsomely than Leo Tolstoy.